Harassment, wrongful evictions, and long transfer delays in San Francisco’s Shelter-in-Place hotels

Public records reveal even the city's best shelters were rife with problems

Sheltering In Place

In April 2020, San Francisco launched its first Shelter-in-Place (SIP) hotel sites aimed at providing non-congregate shelter options for the thousands of homeless residents particularly vulnerable to COVID-19.

Critics were frustrated by the program’s slow rollout, limited availability, and premature termination, but the effort was nevertheless touted as a “historic commitment” by the city, offering wrap-around services and linkages to housing, and seeing high acceptance rates from people living on the street who previously relied largely on long waitlists for crowded congregate shelters.

The program wound down in 2022 despite an ongoing pandemic and the city’s continued desperate need for quality shelter. Along with the closure of the Tenderloin Linkage Center, its termination marked a significant loss of critical services for unhoused people as the city shifted away from services and towards criminalization.

A Campaign of Blame

Many of the residents who exited SIP hotels became homeless again, facing worse shelter options and a relentless onslaught of homeless sweeps.

In December 2022, a federal court heard arguments that these sweeps violate homeless residents’ 4th and 8th Amendment rights and subsequently ordered San Francisco to stop displacing people until it has enough shelter and housing to offer.

In response, city officials appealed the order, criticized the judge, and launched a campaign of blame against SF’s unhoused population, framing the problem not as one of a city failing to provide services but of homeless people refusing to accept them. The campaign was punctuated by a rally organized by city officials to protest the court, remarks by District Attorney Brooke Jenkins that homeless people should be made ‘uncomfortable’, and a tweet by Mayor Breed claiming that 60% of people refuse shelter.

The city’s renewed focus on service refusals and what it calls “voluntary homelessness” places the blame on homeless people while ignoring the evidence that:

There is currently no way for a homeless person in San Francisco to voluntarily access shelter.

The city’s homeless sweeps teams head out with only enough shelter beds available for around 40% of an encampment.

The services offered at encampment sweeps are often not suitable for recipients.

This last point is critical: while the city must legally offer shelter during a homeless sweep, there’s no requirement about how suitable the shelter must be. Historically, the city has used this loophole to comply with the law by offering one-night beds in inaccessible congregate settings with tight restrictions. Police Commissioner Petra DeJesus summed it up in a 2019 hearing: “If they refuse a one-night stay, they lose their belongings and their tents, and that's a high price to pay, especially with the winter we just had.”

People accept services if it makes rational sense for them to do so. City officials know this, but rather than improve services to meet the need, they’ve decided it’s simpler to claim the need doesn’t exist at all.

Research on shelter acceptance cited by the city itself outlines how service refusals in fact represent barriers to entry such as inaccessibility for people with disabilities, restrictions on pets, partners, or property, chaotic congregate settings, long wait times, short limits on stays, and difficulties with securing permanent housing for outgoing residents.

Zal Schroff, attorney for the plaintiffs in the lawsuit against the city, put it this way to the SF Standard:

“The idea that unhoused people are refusing shelter in large numbers is completely unfounded and contradicts the evidence submitted to the court that underpins the injunction.”

A Statistical Game

As inadequate as the city’s shelter offers are, many people do accept them, and, unsurprisingly, the more suitable the offer, the higher the acceptance rate. Today, the Healthy Streets Operation Center (HSOC) offers a mix of shelter types during sweeps, but the majority of the city’s stock consists of inaccessible congregate emergency shelter beds. It’s not in the city’s interest to break this number down by shelter type, but some data does exist.

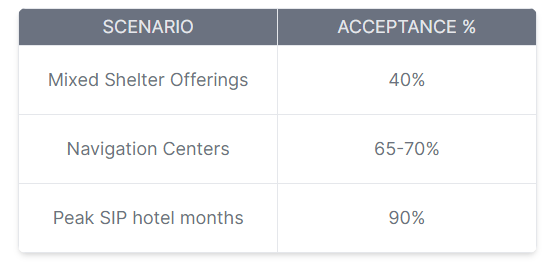

Acceptance rates for Navigation Centers, which offer better quality services and longer stays than traditional shelters, lie in the 65-70% range, in spite of the fact that historically only 14% of people are connected to permanent housing.

Even more striking, after the city opened its SIP hotels in 2020 and “began operating strongly again” with the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing (HSH) as a “key partner providing the resources to outreach and bring people inside,” a performance audit showed 90% acceptance rates of services, “leading to the most significant change in street culture in the TL in 20 years.” In other words, leading with services that respond to needs rather than attaching shelter offers to enforcement engagements leads to better success rates.

Similarly, when shelter-in-place hotel rooms were being offered in July 2020, 83% of people engaged at encampments chose to move indoors. But by December, when the hotels stopped accepting intakes, only 30% accepted.

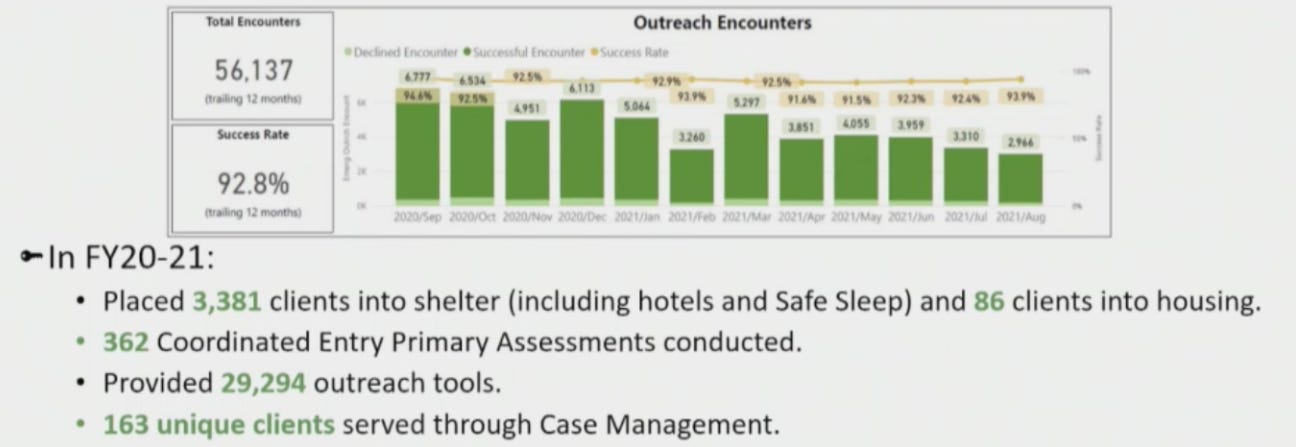

Likewise, HSH data regularly shows over 90% success rates in outreach encounters for non-shelter services, emphasizing that people are desperate for services that genuinely meet their needs.

The city knows that removing barriers to entry is critical for increasing acceptance rates; it’s why Navigation Centers were developed in the first place. But officials pick and choose which statistic to advertise depending on what’s politically convenient. Need to show that the Mayor is successfully providing services? Advertise the 90% rate. Being sued in federal court and need to pass the blame to the homeless? Advertise the 40% rate.

In short, people accept services if it makes rational sense for them to do so. City officials know this, but rather than improve services to meet the need, they’ve decided it’s advantageous to claim the need doesn’t exist at all.

Hostile Hotels

To punctuate the cynicism of the city's campaign of blame, I obtained public records showing that even in SIP hotels, with their superior services and high acceptance rates, guest logs were rife with complaints of harassment, wrongful evictions, and long transfer delays.

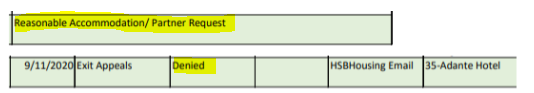

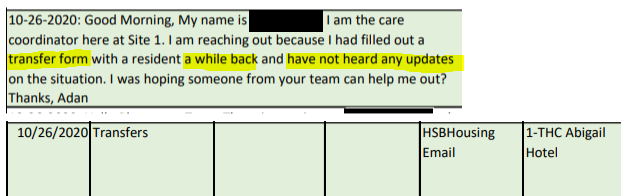

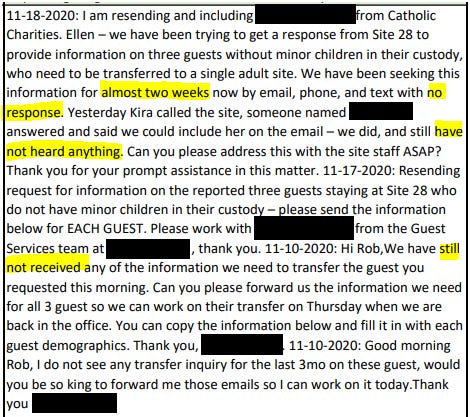

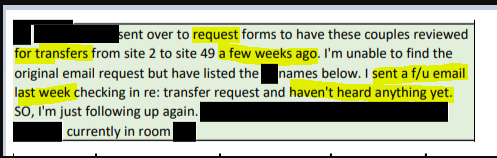

In 2020, the COVID-19 Command Center published its Manual and Guidance for Site Operators, outlining steps for guests and staff to file and respond to complaints, requests, and appeals related to services at SIP hotel sites (p. 47-54). Staff are required to document the nature and outcomes of these filings, which they did in guest logs.

I obtained those logs for the second half of 2020. Here’s what the complaints cite:

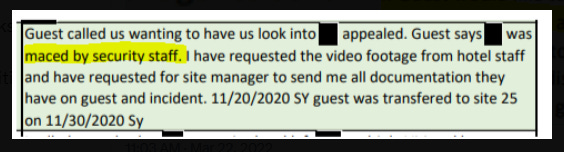

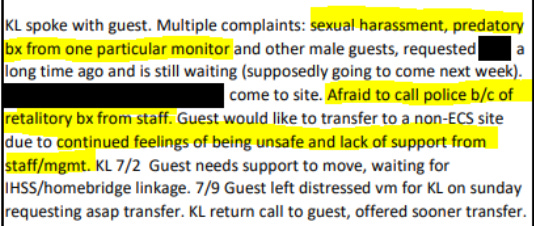

Assault, harassment, and predatory behavior by staff and fear of retaliation if guests reported the mistreatment to police:

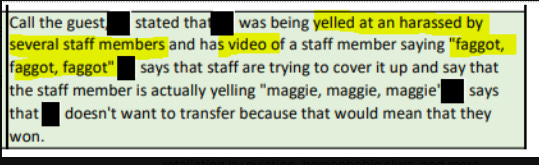

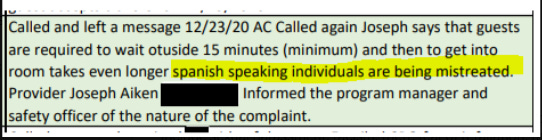

Homophobic and racist discrimination, including slurs and mistreatment of Spanish speakers:

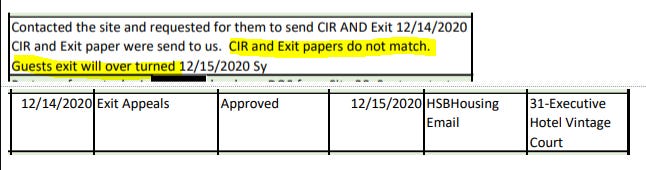

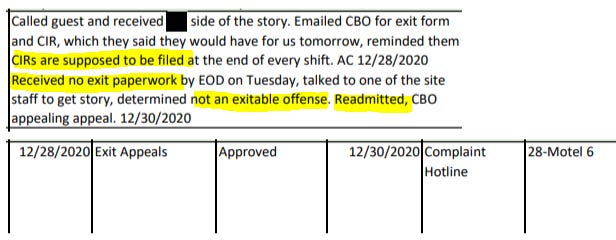

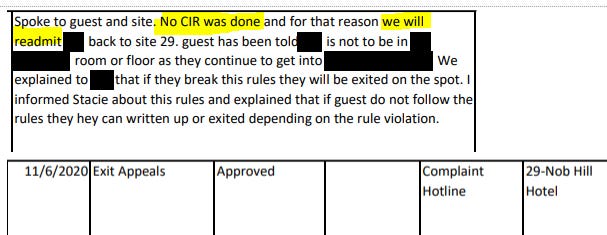

A pattern of wrongful evictions of guests due to basic mismanagement, failures to fill out Critical Incident Reports (CIRs), and non-exitable offenses:

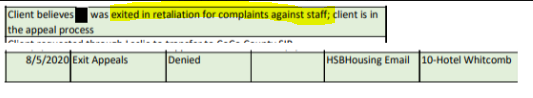

An accusation of eviction as retaliation for complaints against staff:

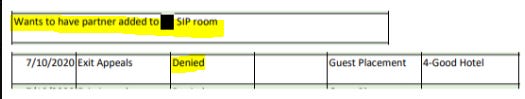

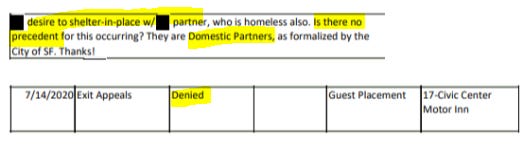

Denials of guest requests to shelter in place with partners, even in a case of domestic partnership:

And - to top it all off - a pattern of long transfer delays, leaving guests subject to unsafe conditions for weeks before obtaining new placements:

This pattern of harassment and mismanagement occurred in the city’s most robust shelter offerings, which it has since shuttered in favor of worse options.

Meanwhile, thousands of unsheltered people remain on the street, facing encampment sweeps, long waitlists for poor services, and now a smear campaign to cover for the city’s inability to provide a basic human right.